What do these neurons hear as they listen to other neurons talking? That depends on the language being spoken—or the identity of the neurotransmitter that is released. Although some research has revealed exceptions, the vast majority of neurons are currently thought to be monolingual—they can only release one type of neurotransmitter.

Most of these (~80%) release the excitatory transmitter glutamate, which promotes spiking in target neurons, whereas other neurons release GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter that functions to prevent spiking. Other neurotransmitters include:

- Dopamine (the loss of which leads to Parkinson’s Disease)

- Serotonin

- Acetylcholine

- Glycine

More excitation than inhibition

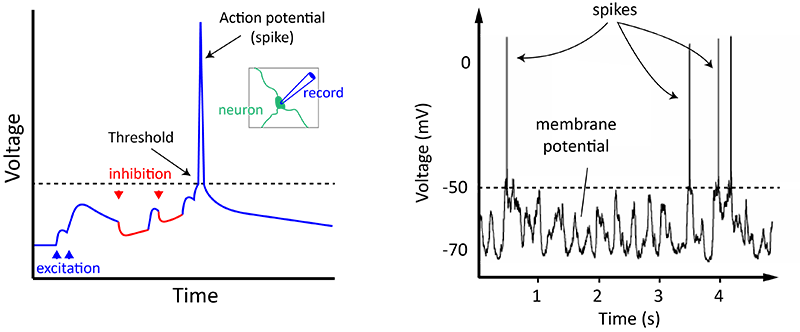

Neuronal communication is exquisitely regulated as a balance between excitatory and inhibitory influences (Fig 2). A given neuron receives hundreds of inputs, almost exclusively on its dendrites and cell body. These inputs add and subtract in a constantly evolving pattern, depending on what the brain is thinking. This is a process called synaptic integration, which determines whether a neuron becomes active.

In order to become active, the total input must reach a threshold at which excitation outweighs inhibition enough. Only at this point will the receiving neuron spike, adding its voice to the conversation by releasing its own neurotransmitter.

Neurons are diverse

Neurons aren’t all the same; for starters, they release different neurotransmitters. Moreover, several different subclasses of neurons can use the same transmitter. These different subclasses seem to be suited to different tasks in the brain, although we don’t fully know yet what those tasks are. One major goal of contemporary neuroscience is to understand the extent of this diversity.

How many different types of neuron are there (and how can we define a “type” of neuron)? What do they all do? Are particular types more important than others in various diseases, and can we target them for therapies?

The ongoing genetic revolution has made these questions more addressable than ever before, yet we still have a long way to go. Once you appreciate this diversity and combine it with the fact that there are 86 billion neurons (plus at least as many glia!) you can begin to understand why we still have much more to discover about how brains work.